Good Friday + Easter Sunday

It Doesn’t Add Up!

Downloads

Good Friday + Easter Sunday: It Doesn’t Add Up!

About one billion Protestants and another billion Catholics believe that Jesus Christ was crucified and entombed on a Friday afternoon—“Good Friday”—and raised to life again at daybreak on Easter Sunday morning, a day and a half later.

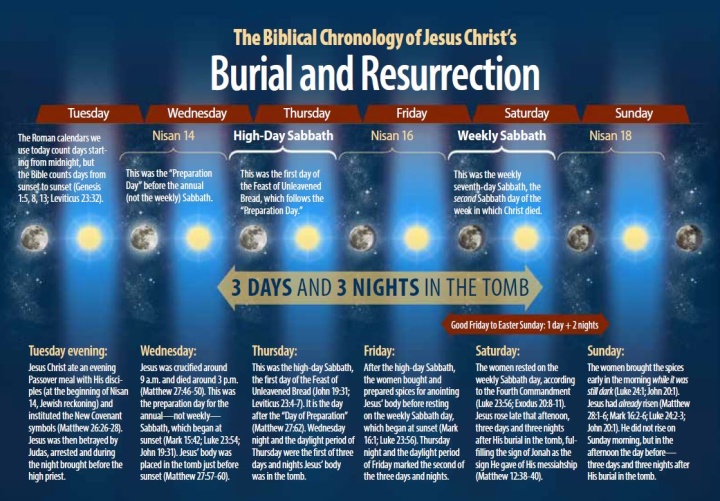

Yet when we compare this to what Jesus Himself said about how long He would be in the tomb, we find a major contradiction. How long did Jesus say He would be in the grave? “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:40, emphasis added throughout).

The context in which Jesus Christ said these words is important. The scribes and Pharisees were demanding a miraculous sign from Him to prove that He was indeed the long-awaited Messiah. “But He answered and said to them, ‘An evil and adulterous generation seeks after a sign, and no sign will be given to it except the sign of the prophet Jonah’” (verse 39).

This was the only specific sign Jesus gave that He was the promised Messiah: “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.”

Traditional timing doesn’t add up

The Gospels are clear that Jesus died and His body was hurriedly placed in the tomb late in the afternoon, just before sundown marking the beginning of a Sabbath (John 19:30-42).

By the traditional “Good Friday–Easter Sunday” timing, from Friday sundown to Saturday sundown is one night and one day. Saturday night to Sunday daybreak is another night, giving us a total of two nights and one day. So where do we get another night and two days to equal the three days and three nights Jesus said He would be in the tomb?

This is definitely a problem. Most theologians and religious scholars try to work around it by arguing that any part of a day or night counts as a day or night. Thus, they say, the final few minutes of that Friday afternoon were the first day, all day Saturday was the second day, and the first few minutes of Sunday morning were the third day.

Sounds reasonable, some conclude.

The trouble is, it just doesn’t work. That only adds up to three days and two nights, not three days and three nights.

Also, John 20:1 tells us that “on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene went to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb.”

Did you catch the problem here? John tells us it was still dark when Mary went to the tomb on Sunday morning and found it empty. Jesus was already resurrected well before daybreak. Thus He wasn’t in the tomb any of the daylight portion of Sunday, so none of that can be counted as a day!

That leaves us with, at most, part of a day on Friday, all of Friday night, a whole daylight portion on Saturday, and most of Saturday night. That totals one full day and part of another, and one full night and most of another—still at least a full day and a full night short of the time Jesus said He would be in the tomb!

Clearly something doesn’t add up. Either Jesus misspoke about the length of time He would be in the tomb, or the “Good Friday–Easter Sunday” timing is not biblical or accurate.

Obviously both cannot be true. So which one is right?

God-given time reckoning is the key

The key to understanding the timing of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection lies in understanding God’s timetable for counting when days begin and end, as well as the timing of His biblical festivals during the spring of the year when these events took place. It’s not hard to figure out when we look closely at what the Bible says.

We first need to realize that God doesn’t begin and end days at midnight as we now do. That is a humanly devised method of counting time. Genesis 1:5 tells us quite plainly that God counts a day as beginning with the evening (the night portion) and ending at the next evening: “So the evening [nighttime] and the morning [daylight] were the first day.” God repeats this formula for the entire six days of creation.

In Leviticus 23, where God lists all of His holy Sabbaths and festivals, He makes it clear that they are to be observed “from evening to evening” (Leviticus 23:32)—in other words, from sunset to sunset, when the sun went down and evening began.

This is why Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, followers of Jesus, hurriedly placed His body in Joseph’s nearby tomb just before sundown (John 19:39-42). A Sabbath was beginning at sundown (John 19:31), when work would have to cease.

Two kinds of “Sabbaths” lead to confusion

As John tells us in John 19:31: “Therefore, because it was the Preparation Day, that the bodies [of those crucified] should not remain on the cross on the Sabbath (for that Sabbath was a high day), the Jews asked Pilate that their legs might be broken [to hasten death], and that they might be taken away.”

In the Jewish culture of that time, the chores of cooking and housecleaning were done on the day before a Sabbath to avoid working on God’s designated day of rest. Thus the day before the Sabbath was commonly referred to as the “preparation day.” Clearly the day on which Christ was crucified and His body placed in the tomb was the day immediately preceding a Sabbath.

The question is, which Sabbath?

Most people assume John is speaking of the regular weekly Sabbath day, observed from Friday sunset to Saturday sunset. From John’s clear statement here, most people assume Jesus died and was buried on a Friday—thus the traditional belief that Jesus was crucified and died on “Good Friday.”

Most people have no idea that the Bible talks about two kinds of Sabbath days—the normal weekly Sabbath day that falls on the seventh day of the week (not to be confused with Sunday, which is the first day of the week), and seven annual Sabbath days, listed in Leviticus 23 and mentioned in various passages throughout the Bible, that could fall on any day of the week.

Because traditional Christianity long ago abandoned these biblical annual Sabbath days (as well as the weekly Sabbath), for many centuries people have failed to recognize what the Gospels plainly tell us about when Jesus Christ was crucified and resurrected—and why “Good Friday–Easter Sunday” never happened that way.

Most people fail to note that John explicitly tells us that the Sabbath that began at sundown immediately after Jesus was entombed was one of these annual Sabbath days. Notice in John 19:31 his explanation that “that Sabbath was a high day”—“high day” being a term used to differentiate the seven annual Sabbaths from the regular weekly Sabbath days.

So what was this “high day” that immediately followed Jesus Christ’s hurried entombment?

The Gospels tell us that on the evening before Jesus was condemned and crucified, He kept the Passover with His disciples (Matthew 26:19-20; Mark 14:16-17; Luke 22:13-15). This means He was crucified on the Passover day.

Leviticus 23, which lists God’s festivals, tells us that on the day after the Passover a separate festival, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, begins (Leviticus 23:5-6). The first day of this Feast is “a holy convocation” on which “no customary work” is to be done (Leviticus 23:7).

This day is the first of God’s annual Sabbaths in the year. This is the “high day” of which John wrote. Several Bible commentaries, encyclopedias and dictionaries note that John is referring to an annual Sabbath here rather than the regular weekly Sabbath day.

Passover began at sundown and ended the following day at sundown, when this annual Sabbath began. Jesus kept the Passover with His disciples, then was arrested later that night. After daybreak the next morning He was questioned before Pontius Pilate, crucified, then hurriedly entombed just before the next sunset when the “high day,” the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, began.

It should be noted that the Jews often generically referred to the whole Feast of Unleavened Bread as “Passover,” explaining why the day of Christ’s trials and crucifixion is even called “the Preparation Day of the Passover” (John 19:14)—that is, of the first Holy Day or annual Sabbath of the Passover week.

Leviticus 23 tells us the order and timing of these days, and the Gospels confirm the order of events as they unfolded.

Jesus crucified on Wednesday, not Friday

It can be shown that in the year Jesus was crucified the Passover meal must have been eaten on Tuesday night and that Wednesday sundown marked the beginning of the “high day,” the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread.

Jesus, then, was crucified and entombed on a Wednesday afternoon, not on Friday. Proof of this can be found in the Gospels themselves.

Let’s turn to a seldom-noticed detail in Mark 16:1: “Now when the Sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices, that they might come and anoint Him.”

In that time, if the body of a loved one was placed in a tomb rather than being buried directly in the ground, friends and family would commonly place aromatic spices in the tomb alongside the body to reduce the smell as the remains decayed.

Since Jesus’ body was placed in the tomb just before that high-day Sabbath began, the women had no time to buy those spices before the Sabbath. Also, they could not have purchased them on the Sabbath day, as shops were closed. Thus, Mark says, they bought the spices after the Sabbath—“when the Sabbath was past.”

But notice another revealing detail in Luke 23:55-56: “And the women who had come with [Christ] from Galilee followed after, and they observed the tomb and how His body was laid. Then they returned and prepared spices and fragrant oils. And they rested on the Sabbath according to the commandment.”

Do you see a problem here? Mark clearly states that the women bought the spices after the Sabbath—“when the Sabbath was past.” Luke tells us that the women prepared the spices and fragrant oils, after which “they rested on the Sabbath according to the commandment.”

So they bought the spices after the Sabbath, and then they prepared the spices before resting on the Sabbath. This would be a clear contradiction between these two Gospel accounts—unless two Sabbaths were involved!

Indeed when we understand that two different Sabbaths are mentioned, the problem goes away.

Mark tells us that after the “high day” Sabbath, which that year must have begun Wednesday evening at sundown and ended Thursday evening at sundown, the women bought the spices to anoint Jesus’ body. Luke then tells us that the women prepared the spices—activity which would have taken place on Friday—and that afterward “they rested on the Sabbath [the normal weekly Sabbath day, observed Friday sunset to Saturday sunset] according to the commandment.”

By comparing details in both accounts along with a proper understanding of three days and three nights, we can clearly see that two different Sabbaths are mentioned along with a workday—Friday—in between. The first Sabbath was a “high day”—the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which fell on a Thursday that year. The second was the weekly seventh-day Sabbath.

The original Greek in which the Gospels were written also plainly tells us that two Sabbath days were involved in these accounts. In Matthew 28:1, where Matthew writes that the women went to the tomb “after the Sabbath,” the word Sabbath here is actually plural and should be translated “Sabbaths.” Bible versions such as Alfred Marshall’s Interlinear Greek-English New Testament, Green’s Literal Translation, Young’s Literal Translation and Ferrar Fenton’s Translation make this clear.

When was Jesus resurrected?

We have seen, then, that Jesus Christ was crucified and entombed on a Wednesday, just before an annual Sabbath began—not the weekly Sabbath. So when was He resurrected?

John 20:1, as noted earlier, tells us that “on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene went to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb.” The sun had not yet risen—“it was still dark,” John tells us—when Mary found the tomb empty.

Obviously, then, Jesus was not resurrected at sunrise on Sunday morning. So when did that happen? The answer is plain if we simply read the Gospels—especially Jesus Christ’s own words—and accept them for what they say.

“For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth,” said Jesus (Matthew 12:40).

As we have seen, Jesus must have been entombed—placed “in the heart of the earth”—just before sundown on a Wednesday. All we have to do is count forward. One day and one night brings us to Thursday at sundown. Another day and night brings us to Friday at sundown. A third day and night brings us to Saturday at sundown.

According to Jesus Christ’s own words, He would have emerged from the grave three days and nights after He was entombed, at around the same time—near sunset. Does this fit with the Scriptures? Yes—as we have seen, He was already risen and the tomb empty when Mary arrived “while it was still dark” on Sunday morning.

While no one was around to witness His resurrection (which took place inside a sealed tomb watched over by armed guards), Jesus Christ’s own words and the details recorded in the Gospels show that it had to have happened three days and three nights after His burial, near sunset at the end of the weekly Sabbath.

Try as one might, it is impossible to fit three days and three nights between a late Friday burial and a Sunday morning resurrection. The Good Friday–Easter Sunday tradition simply isn’t true or biblical. But when we look at all the details recorded in the Gospels and compare them with Jesus’ own words, we can see the truth—and it matches perfectly.

The words of the angel of God, who so startled the women at the empty tomb, are proven true: “Do not be afraid, for I know that you are looking for Jesus, who was crucified. He is not here; he has risen, just as he said” (Matthew 28:5-6, New International Version).

Let’s not cling to religious traditions and ideas that aren’t supported by Scripture. Be sure that your own beliefs and practices are firmly rooted in the Bible. Are you willing to make a commitment to worship God according to biblical truth rather than human tradition?

Centuries-Old Documents Show Evidence for a Wednesday Crucifixion

Did you know there is additional historical evidence for a Wednesday crucifixion? Although it was a minority position and ran against the prevailing teachings of the Roman church, some early historical documents acknowledge a Tuesday night Passover, a Wednesday crucifixion and a Saturday afternoon resurrection—matching the biblical record.

Around the year 200, a document purporting to pass on apostolic instruction, called the Didascalia Apostolorum, mentions that the last Passover of Jesus Christ and His disciples was on a Tuesday night.

This document states: “For when we had eaten the Passover on the third day of the week at even [Tuesday evening], we went forth to the Mount of Olives; and in the night they seized our Lord Jesus. And the next day, which was the fourth of the week [Wednesday], He remained in ward in the house of Caiaphas the high priest” (emphasis added throughout).

Paradoxically, the text goes on to mention that Jesus was crucified on a Friday—showing great confusion about the dates, for the biblical account clearly states that Christ was crucified in the daylight period following the night of that Passover meal and arrest. Nonetheless, the document demonstrates that Passover was then understood by some to have been on Tuesday evening, which would place the crucifixion on the next day, Wednesday.

Epiphanius (A.D. 367-403), the bishop at Salamis, wrote that “Wednesday and Friday are days of fasting up to the ninth hour because, as Wednesday began the Lord was arrested and on Friday he was crucified.” As we can see, even though the prevailing view was that Friday was the day of the crucifixion, Wednesday was known as the day of Christ’s arrest (happening as it did in the early predawn hours that day).

By the fifth century, Easter Sunday celebrations were widespread. However, a church historian of the time named Socrates notes in a section of his history titled “Differences of Usage in Regard to Easter” that some Christians celebrated the resurrection on the Sabbath rather than on Sunday. As he put it, “Others in the East kept that feast on the Sabbath indeed.”

Bishop Gregory of Tours (538-594), although himself believing in a Sunday resurrection, noted that many believed Jesus rose on the seventh day of the week, stating, “In our belief the resurrection of the Lord was on the first day, and not on the seventh as many deem.”

So rather than a monolithic acceptance of the Good Friday–Easter Sunday scenario, there was confusion about the timing of Christ’s crucifixion in early centuries. Moreover, these historical records show that a minority of Christians during that time understood the biblical timing of a Tuesday evening Passover, a Wednesday crucifixion and a late Saturday afternoon resurrection.